By Hannah Goeselt, Library Assistant

In my last blog post I introduced one of the grandfather clocks (‘clock 007’) held here at the MHS, as well as its clockmaker, Joshua Wilder. In this next post we will explore some of the other craftspeople that contributed to the creation of this piece.

The process that goes into creating the finished piece is complex and involves many distinct types of artisans, of which the internal brass movements is only one contributing piece. The base components themselves involved purchasing brass casts from a local foundry, and sheet iron dial plates imported from Boston. So too the outer casing, iron weights, decorative painting, protective glass, and crowning metal finials must be outsourced and brought together to create the final clock, either by the clock movement manufacturer or as was sometimes the case by the cabinetmaker.

The wood casing that houses the clock movements is one of the more visible qualities in the final product. This particular one was attributed to Abiel White (1766-1844), a cabinetmaker from Weymouth, during the clock’s conservation and restoration in 2011-13. White was a long-time collaborator of Wilder’s, though he also worked with other clockmakers in the region in housing their brass clock movements in mahogany or pine. Attributions to him or his workshop, when not signed, are often based on construction techniques that are peculiar to him, such as using textured paper to seal together board-seams, double “dovetail” notches to attach the hood to the case, and a construction technique that uses numbered pieces fit together in a clockwise pattern. While currently hidden from view, these qualities were uncovered during its conservation and were very helpful in identifying White’s work.

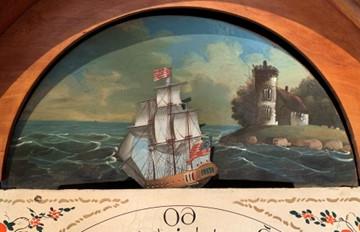

To me, the most eye-catching feature is the mechanism set directly above the clockface. Here, a painted seascape in a semi-circle, or lunette, depicts a coastline with an old stone building situated on a grassy outcrop and what may be a small burying ground with three gravestones. Set in front of the scenery is an articulated three-masted frigate that teeters gently to and fro with the ticking of the seconds, an upper extension of the clock’s pendulum hidden behind the door of the case. The vessel waves a 13-star Cowpens variant of the US flag from its stern, and from its main topmast flies the first Naval Jack (the “don’t tread on me” rattlesnake, an anachronistic addition, is absent). These details seem to indicate that the moving dial is meant to represent a ship from the Continental Navy, though the exact design of both flags have contested histories of their actual use in the Revolutionary War. Rather, this is a 19th century vision of national origin-building, made more within the historical context of the War of 1812.

Likely imported from an artisan in Boston, the rocking ship dial is seen in multiple other examples from this period and region, with its popularity beat only by a painted disk that rotates through the phases of the moon. A brief look into the Boston ornamental painting business in the 1790s through the first three decades of the 19th century shows a small collection of highly specialist artisans who worked closely with and depended heavily on commissions from the much larger furniture and clock making industries. While much of the work remains unsigned, some individuals may be identified based on the clockmakers they were known to work regularly with. Names of Boston decorative artists such as John Ritto Penniman, John Minott, Samuel Curtis and Spencer Nolen are some of the more researched today, but certainly not the extent of the community in the period.

As for provenance, there is no official recording of when and from where the Society acquired this clock, other than its old MHS artifact number, 0979. Most of the MHS’s clocks were donated in the 1960s and ‘70s, with a couple coming to us in the early 1920s; the earliest recorded purchased from the manufacturer directly in 1857. Checking the piece itself for information proved equally fruitless. Other than a small clipping that outlines Wilder’s biography, no interior markings offer clues to its journey here. If we were lucky, the presence of ephemeral bills of sale or a creator’s name inscription would provide hints as to its past.

If you are interested in learning more on the inter-related industries at work in creating clocks in New England, a great starting point is Paul J. Foley’s “Biographies of Patent Timepiece Makers, Ornamental Painters, Cabinetmakers, and Allied Craftsmen” pp.207-339, in his monograph Willard’s Patent Time Pieces (2002).

BIB:

Jobe, Brock, Gary R. Sullivan, and Jack O’Brien. Harbor & Home: Furniture of Southeastern Massachusetts, 1710-1850, University Press of New England, 2009. (Oversize NK2435.M34 J55 2009)

Forman, Bruce R. “The American White Painted Dial”. The Decorator: Journal of the Historical Society of Early American Decoration 50 no. 1 (Fall/Winter 1995-96): 7-24. 1995 Fall.pdf (hsead.org)

Foley, Paul J. “Ornamental Painters” in Willard’s Patent Time Pieces: A History of the Weight-Driven Banjo Clock, 1800-1900, Norwell, MA: Roxbury Village Publishing, 2002. 178-183. (NK7500.B35 F65 2002)